文部科学省が「通知(法的拘束力の無いお知らせ)」という形で2009年に禁止ということにしていた、小中学校へのスマートフォンの持ち込みを、禁止ではないという形に修正する方向で検討に入ったそうです。

小中学校への携帯電話の持ち込みについて、柴山文部科学大臣は、災害が起きた際の児童・生徒の安否確認などに必要なケースもあることから、持ち込みを認める方向で検討を進める考えを示しました。

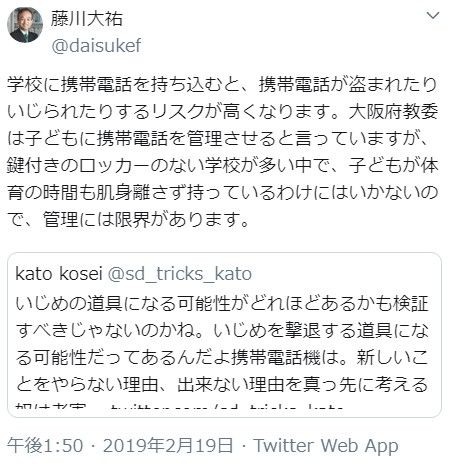

子どもたちの小中学校への携帯電話の持ち込みは、文部科学省、平成21年に出した通知で、教育活動に直接必要がないとして、原則、禁止されています。

こうした中で、大阪府教育庁は、大阪府北部の地震を教訓に、児童・生徒の登下校中に災害が起きても、安否確認をできるようにしようと、持ち込みを認める方針を決め、18日、ガイドラインの素案を公表しました。

柴山文部科学大臣は記者会見でこの素案について、「持ち込み禁止を緩和する一方、適切な使用について児童・生徒や保護者に条件をつけていて、さまざまな懸念や問題に一定の配慮がなされている」と指摘しました。

そのうえで、柴山大臣は、「学校を取り巻く社会環境や児童・生徒の状況の変化を踏まえ、平成21年の通知の見直しを検討していく」と述べ、持ち込みを認める方向で検討を進める考えを示しました。

Conclusion

This article shows how much pupils are already using mobile devices – whether allowed by their school or not. There is clear evidence that many pupils feel that they are deriving educational benefit from the use of their devices. They are using many of the features of their devices and often finding creative ways to employ these features in their schoolwork, both at home and at school.

本稿では、学校公認であろうと非公認であろうと、生徒たちが既に携帯機器をどれだけ使っているかを示した。多くの生徒たちが、自らの携帯電話機は学習において有効であると感じていることは明らかである。彼・彼女らは自身の携帯電話機の持つ多くの機能を利用しており、しばしば自身の学業にそれらの機能を活用するクリエイティブなやり方を発見している。学校においても自宅においても。

The findings raise questions for Secondary leadership and educators. In those schools which still impose a “ban”, is it necessary? Are pupils confused by rules which ban mobile devices but where teachers do unofficially allow their use? Are there more creative ways of presenting the curriculum which would make use of the affordances of mobile devices?

これらの発見は、中学校の学校経営や教員に対して幾つかの疑問を投げかけている。今だに携帯電話機の持ち込みを禁止する必要は、本当にあるのだろうか? 公式には禁止されているはずの携帯電話機をこっそり活用することを教師が黙認しているのは、生徒たちを混乱させるのではないか? 携帯機器がもたらしうるものを活用する、より創造的なカリキュラムの有りようが可能なのではないか? (最後の一文は意訳)

During the time this research has taken place (August–December 2012), there have been significant changes in attitude to mobile devices. Many schools are now giving serious consideration to mobile learning, with some having already distributed one-one devices (Tablets for Schools 2012). This article shows that pupils themselves believe that mobile devices help with their learning and that they are convenient and useful. However, pupils also acknowledge their potential for disruption and for harm. Schools need to be fully aware of the risks and put in place measures to minimise any negative impact.

この研究が行われていた間(2012年の8月から12月)にも、携帯機器の取り扱いについて大きな変化があった。今や多くの学校は携帯機器を活用した学びの推進を真剣に検討しており、既に1:1(one to one computing、在籍する児童生徒全てに1台ずつネット接続機器を持たせること)用デバイスを支給している学校もある。本稿は、生徒たち自身、携帯機器が彼・彼女らの学習を支援してくれる、そしてそれらが便利で役に立つと考えていることを明らかにした。しかしながら生徒たちは、携帯機器が学習の妨げになりうること、誰かを傷つけうることもまた知っている。学校はこれらのリスクに最大限の注意を払い、リスクを最小化するための規定を持たなければならない。

Conclusion

This article shows how much pupils are already using mobile devices – whether allowed by their school or not. There is clear evidence that many pupils feel that they are deriving educational benefit from the use of their devices. They are using many of the features of their devices and often finding creative ways to employ these features in their schoolwork, both at home and at school.

本稿では、学校公認であろうと非公認であろうと、生徒たちが既に携帯機器をどれだけ使っているかを示した。多くの生徒たちが、自らの携帯電話機は学習において有効であると感じていることは明らかである。彼・彼女らは自身の携帯電話機の持つ多くの機能を利用しており、しばしば自身の学業にそれらの機能を活用するクリエイティブなやり方を発見している。学校においても自宅においても。

The findings raise questions for Secondary leadership and educators. In those schools which still impose a “ban”, is it necessary? Are pupils confused by rules which ban mobile devices but where teachers do unofficially allow their use? Are there more creative ways of presenting the curriculum which would make use of the affordances of mobile devices?

これらの発見は、中学校の学校経営や教員に対して幾つかの疑問を投げかけている。今だに携帯電話機の持ち込みを禁止する必要は、本当にあるのだろうか? 公式には禁止されているはずの携帯電話機をこっそり活用することを教師が黙認しているのは、生徒たちを混乱させるのではないか? 携帯機器がもたらしうるものを活用する、より創造的なカリキュラムの有りようが可能なのではないか? (最後の一文は意訳)

During the time this research has taken place (August–December 2012), there have been significant changes in attitude to mobile devices. Many schools are now giving serious consideration to mobile learning, with some having already distributed one-one devices (Tablets for Schools 2012). This article shows that pupils themselves believe that mobile devices help with their learning and that they are convenient and useful. However, pupils also acknowledge their potential for disruption and for harm. Schools need to be fully aware of the risks and put in place measures to minimise any negative impact.

この研究が行われていた間(2012年の8月から12月)にも、携帯機器の取り扱いについて大きな変化があった。今や多くの学校は携帯機器を活用した学びの推進を真剣に検討しており、既に1:1(one to one computing、在籍する児童生徒全てに1台ずつネット接続機器を持たせること)用デバイスを支給している学校もある。本稿は、生徒たち自身、携帯機器が彼・彼女らの学習を支援してくれる、そしてそれらが便利で役に立つと考えていることを明らかにした。しかしながら生徒たちは、携帯機器が学習の妨げになりうること、誰かを傷つけうることもまた知っている。学校はこれらのリスクに最大限の注意を払い、リスクを最小化するための規定を持たなければならない。

Matthew Kearney, teacher educator: no

First, regardless of any ban, students will continue to learn with their phones off-campus, later in life in their tertiary education, and in their professional and workplace learning. Second, if students want to investigate, collect data, receive personalised and immediate feedback, record media, create, compose or communicate with peers in and beyond the classroom, using mobile apps is ideal.

マシュー・カーニー(教員)持ち込みに賛成

第一に、どんなに携帯電話機を禁止したところで、生徒たちは校外では携帯電話機を使って学習をし続けるでしょう。高等教育段階や職場での学習においても同様です。また、生徒たちが何かを調べたり、データを集めたり、パーソナライズドされたフィードバックを直ちに受け取ったり、メディアの情報を記録したり、何かを作ったり、作曲したり、教室の内外で仲間たちとコミュニケートしたりするのに、様々なアプリは理想的な道具です。

Also, if they want to learn at a place, time and pace of their choosing, for example on excursions, or work on projects with friends in more informal spaces like home, on a train or in Facebook groups, mobile devices are needed.

また、もしも彼・彼女らが自分の望む場所や時間、ペースで学習したいと望んだ時、例えば遠足であるとか、自宅や列車内やフェイスブックグループのような場所で友人たちとのプロジェクトを進めようとしたとき、携帯電話機は必須です。